Spider, a striking short film written and directed by C Blake Evernden, opens with an intriguing close up: Feet are submerged in shallow, rippling water. Bright sunlight intensifies the constant movement and dizzying refraction. As we draw away from this first image we see the twigs bark, grasses and detritus of summer — nature renewing, cleaning out the debris. Every slight movement and sound — shimmering leaves, lapping water, birdsong and insects — merge into a sense of being surrounded, even swallowed, by nature in motion.

A winner in the 2018 Best Experimental Short Film Category in the Five Continents International Film Festival, Spider is like an Impressionist’s painting come to life. This is all the more arresting as it’s billed as a horror film, but read on for a more nuanced discussion of genre definitions.

The story’s protagonist, Jennifer Lear (Madison Olsen), sees beauty in entropy. Her impassive gaze is drawn equally to images of decay as well as to the grasses and animal life that surround the film’s farmland setting. We soon find she is responsible for some of the death which surrounds her. This cycle of life and decay is presented with the same unfaltering lyricism and the viewer is asked to step back from their preconceptions.

I was delighted to interview Spider‘s writer/director, C. Blake Evernden.

Spider, lyricism and horror

Q. I wondered first if you can talk just a little about how you achieved the intensity of nature on film.

C. Blake Evernden: The idea for pursuing this particular vision of nature was to give it an omniscient power. I wanted to try and personify its alien aspects, the parts that we never see or just plain overlook. I started using the language and manipulation of cinematic movement and colour to try to give benign natural objects a sense of menace, a sense of the macabre. Portraying a feeling of dread is not something that you put directly on camera, but rather it’s about movement, stillness, texture and colour, things that are off-screen and unmentioned.

Me and my DOP, Gillian Williamson, decided to photograph the elements of nature with shallow depths of field and often in macro detail. I went out on my own for 2 days of B-roll to capture a lot of the macro insect activity and the points of view of the lead character. I wanted to look at nature in the abstract and for the audience to piece it together both impressionistically and texturally.

My lead character has a reverence for nature and also a willingness to die with it. When she steps into her river periodically throughout the film, she can feel the microbes, the bacteria, the natural makeup and communal nature of this fresh water. She feels the exchange of life. When she steps out, there’s this moment of grace, gently moving her feet against the cool grass, a sign of respect.

Reverence for nature: enigmatic protagonist and horse

The whole story was constructed as a visual exploration with no dialogue to drive the storyline. I wanted the photography and the natural world to drive the atmosphere and to make the lead characters’ decisions emotionally understandable, if not cognitively.

Q. The plot very soon takes a dark turn. I would say ‘unexpectedly’ except it is not quite unexpected. There has been no promise that this beauty, this sense of summer brimming over, is necessarily benign. When we see in the rippling, shallow river the unmistakable swirls of blood it seems part of the overall picture, not a contradiction.

Can you talk a little bit about your theme of beauty as predation? Do you think this is a theme of our time?

C. Blake Evernden: I’ve also always held a particular fascination and affinity towards the macabre, towards this pervasive atmosphere amid the possibility or certainty of death, both symbolically and literally.

So, I drew an interest in telling often entirely visual stories that explored what I felt was an interrelation between both nature and the macabre. I began using nature as the ultimate character, both hero and villain; often loving, ethereal and beautiful but also relentless, impersonal and seemingly conscienceless. There’s this great balance in our relationship where the human race is both a symbiotic necessity and a scourge on the natural world that must be shaken off.

I do think that the more the natural world rebels against our ignorance and refusal to adapt that this will grow to be a more important discussion in storytelling circles. I strangely find something beautiful in this impermanence of life and the randomness of our being here. And this led me to an interest in Entropy. Entropy is nature’s tendency to favour disorder. It’s about a lack of predictability, a gradual decline into disorder, that all aspects of nature are constantly breaking down.

Life itself represents a decrease of entropy, or rather a decrease of this random nature. To preserve life is to decrease entropy and ultimately fight against nature. A researcher at the University of Colorado in the field of Bio-Chemistry and Molecular Genetics by the name of Jonathan Mark Davis proposed that maybe aging itself was a form of evolutionary adaptation. But evolution works only when there’s continual turnover of biological material. Simply put, death is a necessity of nature.

So, all these ideas that roamed around in my head is what led me to write and shoot Spider. This is the story of a girl fascinated with both death and life. She finds love in death and is threatened by life. She finds love in the natural world more out of reverence for the constant change of it. She embraces death and is confused by life. In the narrative for the story, she’s a farm girl who begins to relate more to people in death than in life. She finds a boyfriend and kills him in order to have a more meaningful relationship.

I wanted to visually romanticize the idea of natural decomposition. I wanted to see the undisturbed body in the bonds of nature, to see the life’s blood running through the river, to examine, intellectually, this embrace of nature.

Q. In reference to the horror genre in particular, and part of the zeitgeist, I wonder whether Spider is representative of an emerging theme in which nature (and by extension human nature) as enigmatic, an unknown quantity.

I’m thinking of recent movies like The Witch (2015, Robert Eggers) in which a family of settlers breaks away from their community to settle in the midst of a lush wilderness believing it to be a new Eden, and perhaps Calibre (2018, Matt Palmer) in which two city dwellers go on a hunting trip in northern Scotland.

In both cases, as in Spider, nature is beautiful, full of promise, but also foreboding. There is menace in the ambiance of the forest.

Are filmmakers like yourself, then, addressing a broken relationship between humans and nature? How is Spider an expression of particularly 21st Century anxieties?

C. Blake Evernden: Well, I became interested in this idea of Ecophobia, which is the fear of ecological problems and the natural world. Fear of oil spills, rainforest destruction, acid rain, the ozone hole, a fear of everything related to nature that affects our way of life. But it seems to me that this fear, like a multitude of human anxieties, is rather about a fear of control, or rather the inability to control. With every measure, we attempt to control in nature it instead creates more complexities and more dangers. Simply put, nature cannot be controlled.

Simon C. Estok said that ecophobia is an “irrational and groundless hatred of the natural world.” This notion is about our wanting to bend nature, change it, make it seemingly safe and purified for us all to live in. “Our attempts at dominating nature, in other words, are the inevitable reflex of our fear that it can destroy us,” said Matthew Taylor. Estok rejected the idea that nature be perceived as kind and good, when he believed it was, in fact, “morally neutral.”

These are almost purely intellectual and philosophical ideas that I wanted to discuss in Spider because I do feel that nature is something that human kind is constantly at war with instead of attempting find a balance. Within the film, for instance, being able to graphically cut between my lead characters hand running across the face of her boyfriend and then to move to macro photographic explorations of a ladybug on an intricate blade of grass, juxtaposing these moments helps to understand the feeling of the character, a disconnect to what we see as a sanctity of life. I wanted to see if I could romanticize her world view instead of fearing it.

Moral neutrality: Owl and Madison Olsen in Spider

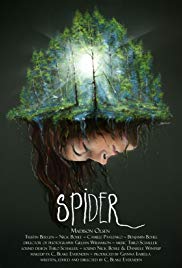

The story is book-ended with the lead character, this farm girl, wading through fresh water. In framing the story this way, I wanted to give her an alien persona where she seems to come from somewhere else and wander the countryside, a being outside of the human race. She looks human, but she’s something else, she sees beauty in different places. I tried to communicate this in the original poster art I created for the film as well, framing her as undergrowth beneath the earth, or perhaps mother Earth itself. Was she a literal creation or rather an aspect of nature itself? I don’t wish one particular reading to be the end of the discussion, I just want it to linger in the viewer. I think that’s one of the main differences between horror and the macabre. Horror jabs, macabre haunts. I was aiming for a haunting love story set amongst the natural world.

Q. Can talk a little about the processes of finding locations (I’ve seen Southern Alberta look so incredibly lush!) and about your partnerships — producer, cinematographer etc. and casting.

C. Blake Evernden: I wrote this film in one morning, based on those feelings I’ve describe previously, and knowing the people that I wanted to work with on the project. I wrote the story with the lead actress already in mind, I wrote it for her. I worked with Madison Olsen, briefly, on my second feature Prairie Dog (2015) where she featured in one sequence in the first act of the film. I loved her look and her naturalness on camera, and I felt that her natural beauty would work as a great visual counterpoint to the more macabre aspects of the story.

I’ve worked with my producer, Gianna Isabella, for a number of years on many projects and when I knew I wanted to shoot this project that summer (a pretty quick turnaround) I knew she could help me make it happen. We have a good working relationship and she knows how to push me to get my days done.

Lastly, my cinematographer, Gillian Williamson, who’s my sister-in-law, I’ve admired her photographic work for years and always wanted to work with her. I thought that she could give the project both the grandeur and the intimacy I was looking for. I’ve served as my own cinematographer for many years, but I wanted the collaboration on this film, and we’re aiming to continue to work together on future projects.

The locations were an aspect I had in mind before I wrote the film. My mom used to summer as a kid at a ranch near Claresholm and I had used that location for some B-roll material in Prairie Dog so I knew that would be my lead characters home. I spend so much time back in the coulees around Lethbridge in the summer, I’ve known the rivers and islands for over 15 years now and I just wrote my experiences into the script, the geography of where I’ve walked and where I’ve lay in the tall grass and watched the clouds roll by.

The one location that was difficult, simply for audio recording purposes, was Park Lake. I knew I wanted to use that location for the bookended sequences of the film, and I’ve used it previously for the opening title sequence in Prairie Dog, but during the summer the families and campers on the opposite side of the lake render most of the on-set sound recording problematic. I needed an isolated, natural soundtrack and so a good deal of that material had to be re-recorded and mixed.

I’ve shot 2 features and 5 short films in Southern Alberta and I always focus the aesthetic and atmospheric heart of those productions around the wide-open distant landscapes. I haven’t grown creatively tired of this natural landscape, rather it fuels my creative interests. I have at least 3 more feature projects that focus on these natural places and so it speaks a great deal to the types of stories that I want to tell.

Read more about C. Blake Evernden and his films on his website.

***

Note to publishers wishing to send reissued classic fiction or new fiction for possible review on this blog, please email me (using ‘Contact Me’ page) to arrange submission. Thanks!

Paul Butler is the author of The Widow’s Fire (Inanna) and the forthcoming Mina’s Child (Inanna, slated for 2020).

Thanks for the insightful interview! The film sounds interesting.

Thanks, Michael! It certainly is.